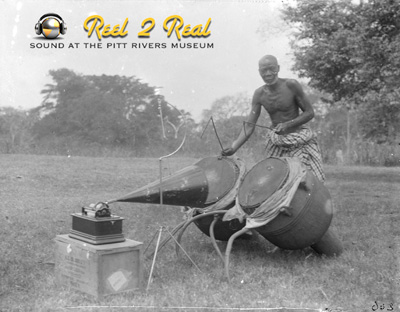

About the Reel to Real Project

No human sense is more neglected in ethnographic museums than sound. The Reel to Real Project (2012-13), funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, set out to make available for the widest use, both in and beyond the museum space itself, the important sound collections of the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford University's Museum of Anthropology and World Archaeology.

No human sense is more neglected in ethnographic museums than sound. The Reel to Real Project (2012-13), funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, set out to make available for the widest use, both in and beyond the museum space itself, the important sound collections of the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford University's Museum of Anthropology and World Archaeology.

Hundreds of hours of unique ethnographic sound, donated to the Museum since the early twentieth century, had been held in storage, known only to a handful of scholars. These sound recordings – which range from children's songs in Britain and Europe to music from South America and the South Pacific, and from improvised water drumming to the sound of rare earth bows in the rainforests of the Central African Republic – were preserved but unavailable to members of the public, teachers, students, or to the communities from which the sound originated. Vitally, the capacity of the sound collections to illuminate the Museum's related artefact and photograph collections remained unexplored.

Drawing on identified expertise and an innovative collaboration with the British Library and the Oxford e-Research Centre, the twelve-month project explored the potential for making the PRM's sound recordings better understood and used within the Museum and beyond it, for the benefit both of general public and future researchers. The main outputs were a public gallery event, two project workshops, and this web resource. Longer term plans, for which more funding will be required, include online access to the entire database of sound material, with online streaming of audio files.

The Pitt Rivers Museum has chosen to retain its sound recordings because they remain of crucial importance to a rounded understanding of related material in the Museum's collections. For instance, sound recordings made by NW Thomas in Nigeria, Louis Sarno in the Central African Republic, Edward Evans-Pritchard in South Sudan, and Diamond Jenness in Melanesia, all form part of larger collections of artefacts and photographs.

At the outset of the project, there was no working database for the collection, and most of the recordings were on inaccessible (and in some cases fragile) formats such as wax cylinder, reel to reel, DAT and audiocassette, that needed to be digitised for preservation before they could be safely heard and further disseminated. Some of the relevant collections had been digitised in the past by the British Library Sound Archive, in particular the NW Thomas cylinders, and they agreed to return this data to the PRM as part of the project. Their expertise in working on the digitised originals (some of which are over one hundred years old) was vital to disseminating the material to new audiences.

Inspiring use of, and engagement with, sound collections

![Lokhim youth playing jew's harp (East Nepal, 8th January 1971) [2008.115.403] Lokhim youth playing jew's harp (East Nepal, 8th January 1971) [2008.115.403]](../images/Jews_harp_2008_115_403-O.jpg) Lokhim youth playing jew's harp (East Nepal, 8th January 1971) [2008.115.403]Not only were the historic recordings not being worked on (the majority being on historical formats that could not be played), they needed to be digitised and catalogued for them even to be heard (whether online or in the Museum's galleries). Digitising and then bringing the Museum's sound collections online allow them to be understood within the context of related object and photograph collections, as well as related anthropological research and literature. It also enables them to be shared and used by other institutions and individuals.

Lokhim youth playing jew's harp (East Nepal, 8th January 1971) [2008.115.403]Not only were the historic recordings not being worked on (the majority being on historical formats that could not be played), they needed to be digitised and catalogued for them even to be heard (whether online or in the Museum's galleries). Digitising and then bringing the Museum's sound collections online allow them to be understood within the context of related object and photograph collections, as well as related anthropological research and literature. It also enables them to be shared and used by other institutions and individuals.

Sound recordings have potential for widespread use by, and engagement with, diverse audiences. Sound is highly portable and can be delivered within museums in a variety of ways, whether through speaker installations, mobile phone applications, or remote triggering devices as people walk through galleries. Recent experimental music events in the gallery spaces (such as the PRM torch-lit evening events), have demonstrated the potential for sound to illustrate object displays, enhance people's experience of the Museum, and allow them to interpret the collections in different ways.

Sound can be used to illustrate object displays that are hard to see directly (for example where there are existing lighting, display height and other sightline problems), broadening awareness and appreciation of displays. Sound recordings can also be made available as a means of enhancing engagement with collections for visually impaired people. To think through these complex ideas and set of potential outcomes, we collaborated with the Oxford e-Research Centre, whose expertise in the area of the digital humanities and making information more broadly available was essential.

As a result of this, a major public event was held on 23 November 2012 to introduce the archival sounds into the Museum galleries, as part of an evening of musical torchlit trails. The project commissioned Mike Day of Intrepid Cinema to film the event and capture some of the atmosphere, and the finished short film can be seen on this wesite.

An early stage project with potential model value for others

Sound archivists acknowledge that recordings can be difficult to work with, especially because they often need to be linked to other types of content (textual, visual) to be fully enjoyed and understood by non-specialist audiences, and also because they need to be worked on in 'real time' (i.e. a 90 minute recording takes at least 90 minutes to listen to while documenting it). However, although the Museum lacks a permanent specialist curator and has not been able to conduct substantive research into its sound collections to date, there are sound archiving models elsewhere to draw upon. So while this was an early stage project, we consider that the Museum and its partners are well situated to develop a model for bringing into use a crucial but neglected resource.

Towards this, the project held a one-day networking workshop for museum and gallery professionals in December 2012, Sound in Museums, where speakers from around the UK came together to discuss projects involving sound in museum and gallery spaces.

Developing partnerships

![Dan Bahadur examining the ethnographer's tape recorder. Gourds (Thul bom) are very characteristic of Thulung rituals. (East Nepal, 31st March 1970) [2008.115.201] Dan Bahadur examining the ethnographer's tape recorder. Gourds (Thul bom) are very characteristic of Thulung rituals. (East Nepal, 31st March 1970) [2008.115.201]](../images/Ritual_2008_115_201-O.jpg) Dan Bahadur examining the ethnographer's tape recorder. Gourds (Thul bom) are very characteristic of Thulung rituals. (East Nepal, 31st March 1970) [2008.115.201]One of the projects main collaborating institutions was the World and Traditional Music Section of the British Library Sound Archive, who not only digitised the fragile wax cylinders but who also offered much advice and expertise at the various workshops and events throughout the project. In partnership with Dr Marina Jirotka and the Oxford e-Research Centre, the project also explored innovative technological solutions to the problem of making sound recordings available online, physically in gallery spaces and also, potentially, in some of the parts of the world from which the music originated. These ideas were discussed in detail with a group of leading technological and creative practitioners at a workshop hosted by the Pitt Rivers and OeRC on December 17 2012. The Museum's partnership with Oxford Contemporary Music (OCM) through our Embedded composer in residence, Nathaniel Mann, was also an important strand to the project, making full use of Mann's creative take on the archival sound collections within the public torch-lit trail evening.

Dan Bahadur examining the ethnographer's tape recorder. Gourds (Thul bom) are very characteristic of Thulung rituals. (East Nepal, 31st March 1970) [2008.115.201]One of the projects main collaborating institutions was the World and Traditional Music Section of the British Library Sound Archive, who not only digitised the fragile wax cylinders but who also offered much advice and expertise at the various workshops and events throughout the project. In partnership with Dr Marina Jirotka and the Oxford e-Research Centre, the project also explored innovative technological solutions to the problem of making sound recordings available online, physically in gallery spaces and also, potentially, in some of the parts of the world from which the music originated. These ideas were discussed in detail with a group of leading technological and creative practitioners at a workshop hosted by the Pitt Rivers and OeRC on December 17 2012. The Museum's partnership with Oxford Contemporary Music (OCM) through our Embedded composer in residence, Nathaniel Mann, was also an important strand to the project, making full use of Mann's creative take on the archival sound collections within the public torch-lit trail evening.

Developing sound collections within institutional strategies

The Reel to Real project has catalogued, digitised, and made available online a generous selection of the main ethnographic (field) sound collections held by the Museum. Although it has been a leader in developing on-line resources for its object and photograph collections (see e.g. http://southernsudan.prm.ox.ac.uk) the Museum's sound collections have remained entirely outside these developments due to the lack of the required expertise to understand both their content and significance. In this way, the project has fed into longer-term plans in three respects. Firstly, in that the Museum is developing and expanding its music education and outreach. Secondly, the Museum has recently begun a 5-year HLF-funded project to re-display and energise the Museum's collection of artefacts connected with performance and music. Cataloguing, digitising and mobilising our sound collections has been a vital step towards that re-display. Our experience has shown that once opened up and shared, sound collections can become a vital new dimension of a museum's interpretation and engagement strategy. And thirdly, the playing of ethnographic sounds has become a consistent feature of evening public events at the Museum, enabling a new perspective on the collections.

Improving the understanding of collections

Many of the Museum's sound collections had not been heard within the Museum for decades, and in some cases since they were donated. Since they were held in several fragile historical formats it was necessary to outsource both the digitisation and specialist restoration work on these recordings to ensure their preservation and future use. This fundamental work makes everything else possible, but cannot be funded from very limited core museum resources. But once properly processed, curators, researchers, and the general public can begin to listen to and assess these unique historical recordings and develop ideas for future projects, exhibitions, and installations.

Amongst the hundreds of hours of ethnographic sound, it is known that much is unique, or extremely rare, and not deposited elsewhere. The Louis Sarno collection from the Central African Republic, for example, is unprecedented in its scope and duration and is linked to a collection of 1200 images held by the Museum that will shed much light on the music and culture of a little-known and threatened community, the Bayaka of Central African Republic. The recordings by Edward Evans-Pritchard, one of the most significant anthropologists of the twentieth century, are almost completely unknown, but will now enable us to understand his fieldwork and important collections of objects and photographs from South Sudan in an entirely new way. Although of mostly poor audio quality, these wax cylinder recordings offer a unique insight into the history of ethnographic fieldwork, and the potential now exists for indigenous communities to engage with their cultural history.